A Conversation with a Mental Health Clinician at the U.S. Southern Border

12 December 2025|Chloe Gunther

Adalberto “Beto” Sanchez is the JRS/USA mental health clinician serving in El Paso, Texas, and Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, as part of Caminar Contigo, the bi-national border response program co-led by JRS/USA and JRS Mexico.

Before January 20, 2025, Beto’s weeks followed a steady rhythm. He and the JRS team visited shelters in El Paso and Ciudad Juárez to offer support. The people he met were arriving in the United States through CBPOne, a mobile application used by asylum seekers to schedule processing appointments at official ports of entry.

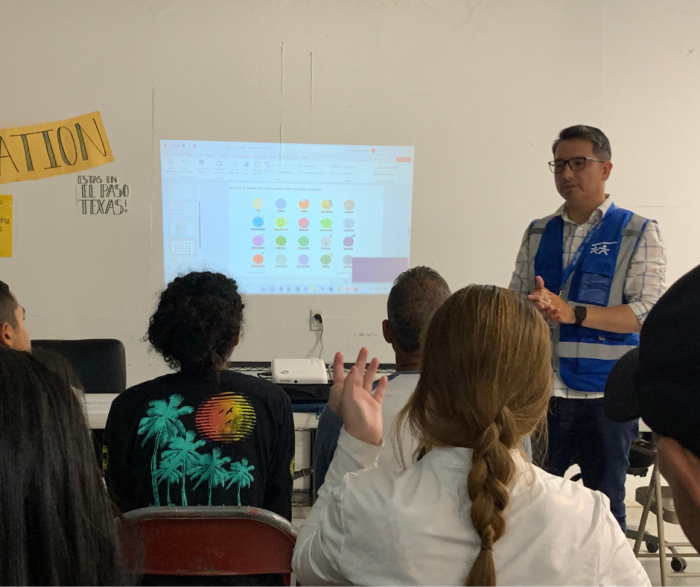

Beto offered crisis counseling for individuals and families to help people cope with the difficulties of migration, as well as group workshops focused on mental health and practical planning. Through the “Life Skills Workshop,” asylum seekers received psychoeducation on coping skills, how to find legal assistance, shelters in their next city, education for their children, and how to use the local food banks. A lesser known but important service he provided was emotional support animal certifications so families could continue traveling with their pets.

Beto offered crisis counseling for individuals and families to help people cope with the difficulties of migration, as well as group workshops focused on mental health and practical planning. Through the “Life Skills Workshop,” asylum seekers received psychoeducation on coping skills, how to find legal assistance, shelters in their next city, education for their children, and how to use the local food banks. A lesser known but important service he provided was emotional support animal certifications so families could continue traveling with their pets.

The situation at the border was already dangerous for those seeking asylum. Many families had survived cartel kidnappings in Mexico and remained fearful even inside shelters. “That’s why some people in Juárez would just go to the U.S. border and surrender themselves; they didn’t feel safe [in Mexico],” he said.

He shared his phone number so people could reach him whenever they were struggling. But at the end of January 2025, when Donald Trump reentered the White House, JRS/USA, partner organizations, and migrants were stunned by how quickly the asylum process was dismantled.

“We had people with CBPOne appointments in February or March. We couldn’t believe the border was just closed,” Beto said. Once the shock passed, people began searching for other ways to survive, including seeking legal aid and more stable residency in Mexico.

The dangers remain. Beto said that just last month authorities discovered a stash house in Northern Mexico where kidnappers were holding migrants. By February, most shelters in El Paso had closed as funding disappeared and no one could enter the United States.

Now, Beto said his work is less predictable day-to-day. He collaborates closely with JRS Mexico in Ciudad Juárez, focusing on mental health support in local shelters. He also stays in touch with those who entered the United States before the closure. Some people call for emotional support, while others need help putting food on the table. Beto regularly goes to the local food bank to pick up baskets.

He shared the story of a single mother from Peru. She had moved to New York but eventually returned to El Paso and rented a house with a group of migrants. There, she began experiencing domestic violence.

Beto does not know how she got his number, but she reached out asking for support. “I try to make sure they know… they still have rights here in the United States,” he said. He helped her look for alternative housing, offering several options from other shelters to renting an apartment herself. “She was so resilient; she had made enough money to find her own place.” He continues providing her with mental health support as she settles into a new home with her child.

Stories like hers remind Beto that migrants are not charity cases, or people to be pitied. They appreciate support but continue moving forward no matter what.

He does find that reaching people can be difficult, partly because of this. Adults living in the United States often work long shifts with little time to do anything outside of work and family responsibilities, including resting or seeking care. “I will get a text early in the morning from someone needing mental health assistance, but they won’t be able to call me until after 7 p.m.,” he said. “I try to be as flexible as I can. I know they do not have the time.”

Negative stereotypes around therapy create another barrier. To counter this, Beto has shared his contact information with local schools and social workers so they can refer people to him. Recently, the majority of those he has worked with are Venezuelan, but he also supports people from Mexico, Honduras, Colombia, and Ecuador.

Looking toward 2026, Beto and his team are reimagining the mental health and psychosocial support program within Caminar Contigo. He is conducting a needs assessment with migrants and volunteers to better understand how U.S. asylum proceedings affect mental health and how MHPSS can be more effectively integrated into that process.

He also hopes to provide more mental health training sessions so more people in the El Paso and Ciudad Juárez communities are equipped to offer crisis counseling.

“While love, companionship and solidarity are important parts of life, what migrants need are professionals,” Beto said. “We must sharpen our skills to be more successful.”