This Black History Month, We Must Recognize Our Own History of Internal Displacement

13 February 2024|Joshua Utter, JRS/USA Outreach Officer

Sarah and her husband worked as farmers in Chibok, Borno State, Nigeria. Aware of the threat of Boko Haram in northern Nigeria, they remained in their hometown as long as they could. When the violence finally reached their community, destroying their livelihood, Sarah and her family fled for their safety. Rather than crossing the international border, they found refuge within Nigeria.

Sarah is one of over the 71 million people who are internally displaced within their own country. As stated by UNHCR, “Internally displaced people (IDPs) have not crossed a border to find safety. Unlike refugees, they are on the run at home.”

Displaced within their home country, internally displaced people are not protected by international refugee law. They remain under the protection of their own country, making it a complex situation for the international community to respond. And while they may have found refuge in their own country, they may still face discrimination, unequal treatment, and a limited response to their needs due to their ethnicity, religion, or social group.

From the Vatican to the United Nations, calls have been made to make sure that internally displaced persons are protected. Jesuit Refugee Service has also made a commitment to address the needs of refugees and internally displaced persons alike.

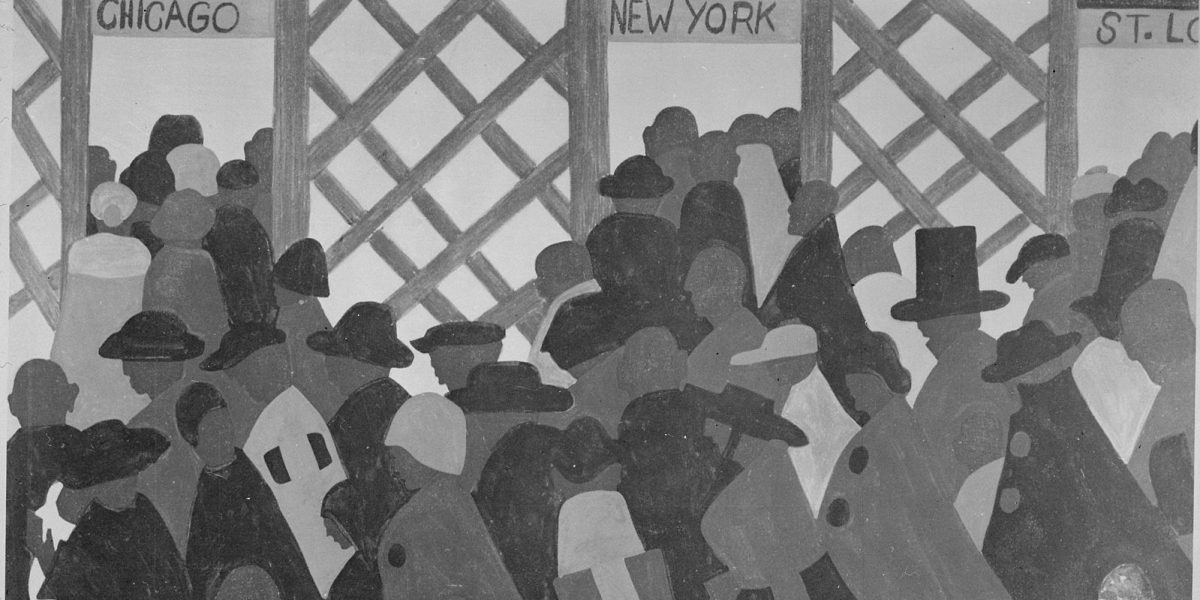

Here in the United States, we might think that internal displacement is an issue for countries overseas, but it is a part of our own past and fairly recent history. During the Great Migration, Black southerners were internally displaced persons seeking freedom, full citizenship, and a better life within the borders of the United States. They left family and loved ones behind, praying that their journey would lead to the promise of stability and security.

The story of Sarah in Nigeria is similar to that of Ida Mae Brandon Gladney. When her husband’s cousin, Joe Lee, was badly beaten by their boss and nearly died, Ida Mae had enough. Heading north to Chicago with her husband, George, and their children, she left the oppressive work of sharecropping and the Jim Crow South behind her. For all the hard labor Ida Mae and George had done for their boss, the pay was insufficient and the threat of violence intolerable. The beating of Joe Lee was the final straw; they had to go find a better life.

The story of Ida Mae and her family is one of millions. According to Isabel Wilkerson, author of “The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration,” six million black southerners migrated between the years 1915 and 1970. Seeking refuge from the servitude of sharecropping, the injustice of Jim Crow laws, the terrorism of white supremacists, and the horrific threat of lynching, they headed north and west to cities that promised freedom. We call this chapter of American history “the Great Migration.”

While some found that stability and security, they still faced discrimination and unequal treatment in their adopted city. Employers still would not hire them simply due to the color of their skin. Housing was limited and crowded due to public policy that ultimately segregated these cities despite the promise of equality. “These were refugee camps created in American cities,” said Isabel Wilkerson in an interview with Krista Tippett.

The United States is still reckoning with its history of white supremacy and injustice towards black Americans. There is still so much work to be done to restore justice. As we recognize Black History Month, in our work to accompany, serve, and advocate for refugees, it is important that we know and recognize this history of displacement and migration within the borders of the United States. We need to know how we arrived here at this moment and what can be done to prevent such instances of displacement from happening again.