Global: African Migration Across the Americas

22 February 2022

Since 2013, an increasing number of African migrants have arrived at the U.S.-Mexico border. The Migration Policy Institute released a report detailing this growing trend, including the experience of African migrants traveling through the Americas and the long-term implications of this pattern.

According to the report, Mexican authorities apprehended 6,641 migrants from Africa, “up approximately 1,000 percent from the 634 such apprehensions in fiscal year 2014.”

In the last five years, as more migrants and asylum seekers arrived in Europe from across North and sub-Saharan Africa, “the management of irregular migration rose to the top of the European Union’s political agenda” making it more difficult for African migrants “to reach North African countries, let alone to enter Europe,” the report notes.

As a result, more African migrants are coming to Brazil and Ecuador from Eritrea, Somalia, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Cameroon, and Ghana. Upon arrival, these individuals are immediately met with cultural, racial, economic and security challenges.

In a conversation with JRS, the two authors of the report, Jessica Bolter and Caitlyn Yates, explained the role which systemic and daily racism play in the experience of African migrants, citing it as one of the main reasons they must continue their journey northward.

Bolter explained that, oftentimes, those arriving in Brazil or Ecuador do not intend on moving to the United States, yet racism in these South American countries subjects African migrants to street harassment and other dangerous situations without any sort of protection. It further compels migrants to continue their search for safer living conditions.

Yet, after deciding to leave and head towards the U.S.-Mexico border, “[African migrants] continue to face racism, whether from government authorities or other migrants,” Bolter says.

This racism is compounded by a lack of preparedness from governments of South and Central American countries to respond to the specific linguistic, cultural, and protection needs of African migrants.

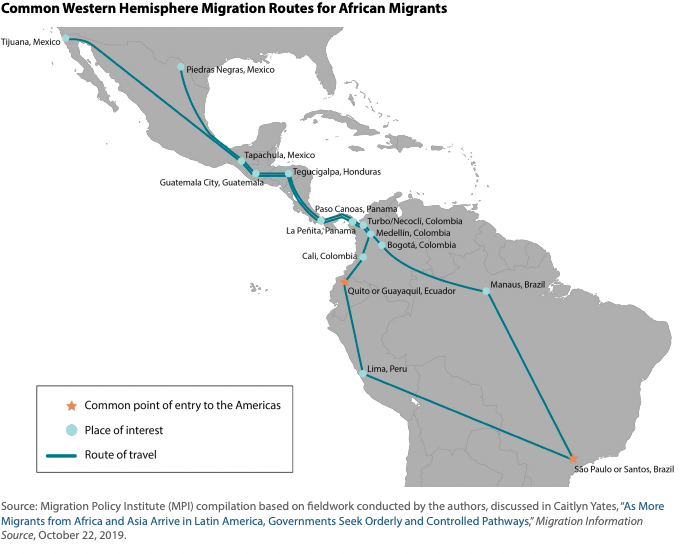

Bolter cited at least nine countries along the route from South America to the United States that are not equipped to accommodate the needs of African migrants.

In these countries, “blackness is not being addressed in any way,” says Yates.

For instance, individuals in Mexico were not able to identify as black on the census until two years ago. Advocates on the ground in Mexico observed worse conditions in detention centers where African migrants were held compared to those for Central American migrants.

Additionally, access to translators and interpreters who can communicate with African migrants is almost nonexistent throughout the nine transit countries. This results in either “really difficult miscommunications or other migrants attempting to interpret ad hoc,” Yates says.

Bolter added that with an increase in migrants from Haiti, Mexican asylum agencies have started using Haitian Creole translators, but this only occurs in small number of cases. “There’s still much work to be done,” she says.

In April 2021, JRS/USA published a joint policy brief — Seeking Protection in a Pandemic — which directly highlighted the difficult conditions for entry which asylum seekers faced around the world. At the time of writing, public health measures, including Title 42 in the US, were used as justification to deny thousands of migrants their right to seek asylum.

The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly stalled African migration but, as some restrictions begin to lift, Yates and Bolter expect to see a return to the increasing trend of African migrants at the U.S.-Mexico border.

“This work requires a more thought-out and comprehensive approach,” while incorporating a policy perspective where countries “collaborate regionally to manage not just this migration flow, but other migration flows that are moving through multiple countries and end up reaching the U.S.-Mexico border.”